By: B. Denise Hawkins

James Madison University Dedicates an Historic Building to Morgan Graduate Joanne Veal Gabbin

“I’ve taken you as far as I can go. Now, you have to go further.”

Those words could have easily confounded the second grader who eagerly consumed the cast-off books her mother, Jessie Smallwood Veal, a part-time domestic worker in Baltimore, brought home when her employers’ children grew tired of them. The daughter, Joanne, looked forward to the pages her mother would read to her over and over — fairytales, the Weekly Reader, lively tales of a beloved elephant named Babar.

But her mother’s declaration wasn’t meant to be a deterrent. Mrs. Veal had already ignited a love of learning in her daughter and instilled in her a respect for the power of the written word, things that would prove to be enduring. But what the seven-year-old Joanne didn’t know at the time was that her mother, her first teacher, had only made it to the fourth grade. For Mrs. Veal, the daughter of sharecroppers in Windsor, North Carolina, education had had to take a backseat to work in the cotton and tobacco fields alongside her 10 siblings.

Dressed in regalia in May of 2021, Joanne Veal Gabbin, Ph.D., of Morgan State University’s Class of 1967, recounted her mother’s words as she delivered the commencement address at James Madison University (JMU). She taught at the university for more than 35 years before retiring this year.

Imagine, Gabbin Hall

Her mother, who “owned seven fully rented row houses” in Baltimore, and her father, who was one of the city’s expert cement masons, lived to see their firstborn graduate from what was then Morgan State College, Dr. Gabbin told her audience. But her parents didn’t live to see the thousands of students she would touch, mentor and encourage during her 50 years of teaching at colleges and universities across the country, or to congratulate her for the award-winning honors program she built at JMU, or to revel in her still growing legacy, which includes having the first named professorship in the Honors College: the Dr. Joanne Gabbin Professorship.

“And, they never would have imagined that their little girl would have a historic university building named after her,” Gabbin said in her address. JMU voted in February 2021 to remove the names of three Confederate military leaders from historic campus buildings to honor five African Americans who had worked for or attended the university. What had been Maury Hall, named for a Confederate naval officer, is now Gabbin Hall. Its new name honors Gabbin and her husband, Alexander Gabbin, Ph.D., who is a professor of accounting and was the first Black to serve as director of the JMU College of Business’ accounting school.

When she received that news, “For a moment I just stopped talking and said to myself, ‘Is this really happening? Is it happening to me and my husband, who are still working and very much alive?’ ” Joanne Gabbin recalls. “We are very much blessed by just working. So it was an honor, and I’m humbled,” she says. For Alexander Gabbin, who called the university’s decision “a bold move,” the new honor “feels unreal.” The couple, natives of Baltimore, has been married for 54 years.

“That meeting changed my life,” says Gabbin, who was accepted to Morgan and awarded a scholarship. “If Morgan hadn’t sent that recruiter to Eastern, many of us probably never would have had the opportunity to go to college.”

— Joanne Gabbin, Ph.D.

A Mother’s Words for the Climb

“When my mother told me that ‘I’ve taken you as far as I can go,’ she was telling me that you are my firstborn, I love you, and you are smart,” says Gabbin, who has called on that encouragement through the years to reassure and propel her as she’s climbed.

Looking back, she says, it helped her navigate the newly integrated halls of Baltimore’s Eastern High School in the years immediately after the decision in Brown v. Board of Education. To Gabbin, one of the handful of bright, Black girls accepted to the public, all-girls school, it was clear that integration didn’t guarantee parity. She knew even then that she wanted a career “in literature and writing,” but at Eastern, she says, that aspiration wasn’t allowed to take root. School clubs and activities, she remembers, were rarely welcoming places for Black girls.

Looking back, she says, it helped her navigate the newly integrated halls of Baltimore’s Eastern High School in the years immediately after the decision in Brown v. Board of Education. To Gabbin, one of the handful of bright, Black girls accepted to the public, all-girls school, it was clear that integration didn’t guarantee parity. She knew even then that she wanted a career “in literature and writing,” but at Eastern, she says, that aspiration wasn’t allowed to take root. School clubs and activities, she remembers, were rarely welcoming places for Black girls.

As her senior year neared a close, Gabbin recalls, Eastern’s plans to guide its girls from high school to college omitted her and her Black classmates. Most of them would be the first in their family to complete the 12th grade. But on a day in April, she and the other daughters of Black strivers made their way to the balcony of the school auditorium. Their principal had invited them to meet with a recruiter from Morgan State College, one of two historically Black colleges in the city.

“That meeting changed my life,” says Gabbin, who was accepted to Morgan and awarded a scholarship. “If Morgan hadn’t sent that recruiter to Eastern, many of us probably never would have had the opportunity to go to college. That’s why I will love Morgan until the day I die.”

A Nurturing Network

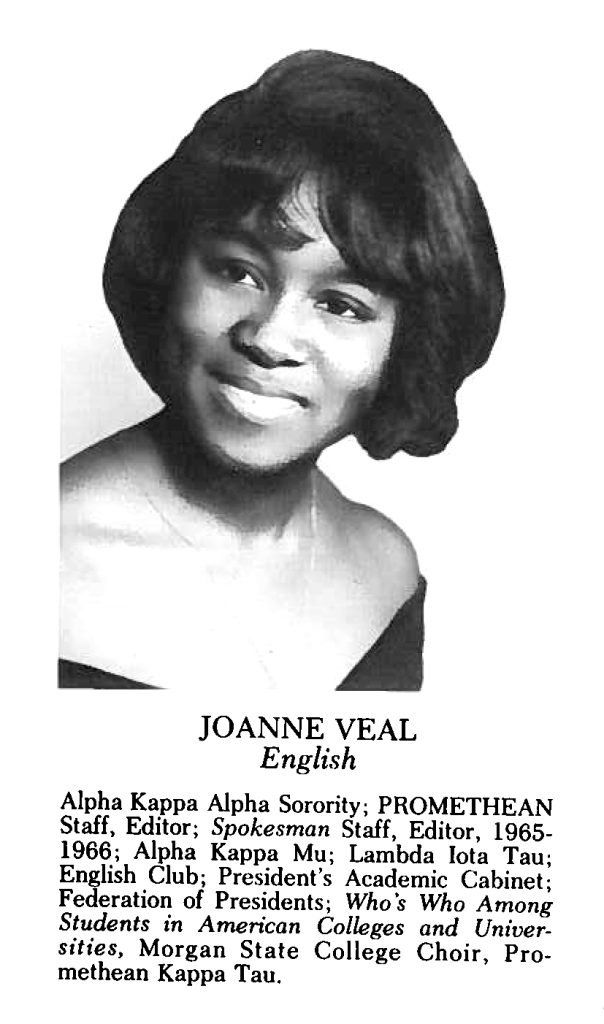

When she arrived on Morgan’s campus in 1963, she found a world of possibilities — and ready opportunities to lead, and to write and tell stories.

When she arrived on Morgan’s campus in 1963, she found a world of possibilities — and ready opportunities to lead, and to write and tell stories.

“I was thinking, there’s nothing that can hold me back now,” says Gabbin, whose voice hints at that decades-old excitement. The eager freshman emerged the feature editor after attending her first meeting of The Spokesman, Morgan’s student paper. By her sophomore year, Gabbin was at the helm as the paper’s editor. The aspiring journalist even reported alongside national media who descended on Baltimore when hundreds of Morganites staged a now-legendary protest to integrate the nearby Northwood Theatre. At the urging of Frances Murphy Henderson, then Morgan’s public relations director and advisor to the campus paper and yearbook, Gabbin stepped up to edit a commemorative yearbook that marked Morgan’s centennial year.

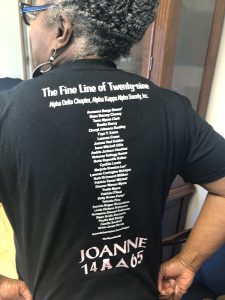

Along the way at Morgan, Gabbin also found time to pledge Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, in 1965.

Morgan was where she found a network of caring Black scholars and writers who likewise took her as far as they could, but not before they equipped her for graduate school and helped prepare the inquisitive, driven and disciplined student for the literary life that was always her ambition.

Gabbin’s voice grows more animated as she does a roll call of “the accomplished and amazing” English professors and writers at Morgan who nurtured and mentored her: “Let’s see. Nick Aaron Ford was head of the English Department then. There was Ruthe Sheffey; Eugenia Collier; Waters Turpin, an outstanding novelist who taught romantic literature. We had Ulysses Lee, who was a co-editor of ‘The Negro Caravan,’ one of the first and best anthologies of Black writing. He also taught modern criticism.”

Gabbin’s voice grows more animated as she does a roll call of “the accomplished and amazing” English professors and writers at Morgan who nurtured and mentored her: “Let’s see. Nick Aaron Ford was head of the English Department then. There was Ruthe Sheffey; Eugenia Collier; Waters Turpin, an outstanding novelist who taught romantic literature. We had Ulysses Lee, who was a co-editor of ‘The Negro Caravan,’ one of the first and best anthologies of Black writing. He also taught modern criticism.”

Eugenia Collier, Ph.D., who retired as the chair of Morgan’s English department in 1996, began a distinguished teaching career at the campus in the early 1950s. But last year, at 93, the still spry and insightful Collier still remembered the newness of faculty life and the patience it took to teach five composition courses a semester until the day came to finally present literature. And she remembers teaching Gabbin.

“I was still getting my feet wet as a professor when Joanne came along,” said Dr. Collier, who had Gabbin as her only student when Morgan introduced a new English literature course as a graduation requirement for seniors. The two met in a large classroom. The coed whom Collier got to know and now calls friend, “was a pretty little girl with thick black hair and sparkly eyes. She laughed easily and still does.” Joanne, she said, was also “eager to learn” and tackled every assignment with verve.

“(Gabbin) is what you’d like all of your students to turn out to be,” said Collier of her student who became a poet, author, literary critic and scholar. “She exceeded any of my expectations for her.”

(Poetry) was a way to tell the truth and a tool to change society.

— Joanne Gabbin, Ph.D.

‘Go Further’

Gabbin credits Morgan’s professors with first stoking her interest in Black literature and poetry, but she notes that her study of the cavalcade of Black writers whose work she later presented to her students came later, when she pursued her Ph.D. at the University of Chicago in the early 1970s. At the time, Morgan, like most other Black colleges and universities, didn’t teach African-American literature, said Collier, who stepped down as chair of Morgan’s English Department in 1996: “It was not valued.”

Gabbin, who titled the first course she taught as a new professor in Chicago, “Revolutionary Self-Consciousness in Black Literature,” realized she “could be more effective as an activist in the classroom than she could be in the streets.”

She made poetry her medium.

“It was a way to tell the truth and a tool to change society,” adds Gabbin, whose name is synonymous with the Furious Flower Poetry Center she founded at JMU in 1994. It is the nation’s first academic center devoted to Black poetry and where she continues to cultivate and promote a new generation of Black poets. Two years before Amanda Gorman, the nation’s first youth poet laureate, made history with her poetry performance at the 2021 U.S. presidential inauguration, Gabbin gave her a national stage when the Furious Flower Poetry Center celebrated its 25th anniversary in Washington, D.C., in 2019.

After spending a lifetime opening doors, Dr. Gabbin ended her tenure at JMU and Furious Flower this summer.

“Looking forward to this new chapter in my life, I think about the models of academic excellence that I found at Morgan. Much of the success I’ve had in the academy I owe to the examples that they set. I birthed Furious Flower and played a part in moving African-American literature, especially poetry, from the margins of consideration in American literature to the very center.”

UMaine Renames Lecture Hall to Commemorate a Former Morgan Dean

The movement for progressive symbolism on college campuses brought a spotlight to another praiseworthy daughter of Morgan State University. In May of last year, the University of Maine System Board of Trustees voted to rename a lecture hall after Beryl Warner Williams, the school’s first Black mathematics graduate and a longtime faculty member and administrator at Morgan.

The movement for progressive symbolism on college campuses brought a spotlight to another praiseworthy daughter of Morgan State University. In May of last year, the University of Maine System Board of Trustees voted to rename a lecture hall after Beryl Warner Williams, the school’s first Black mathematics graduate and a longtime faculty member and administrator at Morgan.

Williams was born and raised in Bangor, Maine, by her mother, who owned a boarding house, and her father, who was a railroad porter. At the University of Maine, she earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree in mathematics, then taught at several colleges in the U.S. South before moving to Baltimore and joining Morgan as an instructor of English then math. In 1970, she was appointed dean of Morgan’s Center of Continuing Education — the first woman to hold that post — and led the center to major advancements until her retirement in 1981.

A lifelong public servant, Williams played a major role in the desegregation of the Baltimore City Public Schools, as a member and officer of the school board from 1974 to 1984, and made significant contributions to many other civic organizations. UMaine awarded Williams an honorary Doctor of Pedagogy in 1972. She passed away in 1999 at the age of 85.

Little Hall — named after a former UMaine president who once served as president of the American Eugenics Society — is now known as Beryl Warner Williams Hall.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It