By: E.R. Shipp

A Morgan Task Force Addresses the Troubling Decline in the University’s Male Student Enrollment

The future of Black males has been a primary concern at Morgan State University since its founding in 1867 as the Methodist school known as Centenary Biblical Institute. Nine Black men made up that inaugural class, as the era of Reconstruction ushered in boundless hope following four years of civil war.

As Morgan approached its 150th anniversary, a young, male computer science student became its 50,000th graduate during the Fall Commencement on Dec. 16, 2016. The exuberant, confetti-laden, pop-up celebration that stunned Joseph L. Jones and his family marked a milestone not just for them but also for the institution whose motto is “Growing the Future, Leading the World.” However, this historic moment, during which Jones had to be encouraged to smile, belied what Mark Barnes, Ph.D., an associate professor of History and Geography at Morgan, had begun to notice: “a growing invisibility” of Black males in his classes. Associate Professor Michael Sinclair was noticing this, too, in the School of Social Work, where “a subtle but persistent decrease” led him to seek ways to attract males to his field.

As Morgan approached its 150th anniversary, a young, male computer science student became its 50,000th graduate during the Fall Commencement on Dec. 16, 2016. The exuberant, confetti-laden, pop-up celebration that stunned Joseph L. Jones and his family marked a milestone not just for them but also for the institution whose motto is “Growing the Future, Leading the World.” However, this historic moment, during which Jones had to be encouraged to smile, belied what Mark Barnes, Ph.D., an associate professor of History and Geography at Morgan, had begun to notice: “a growing invisibility” of Black males in his classes. Associate Professor Michael Sinclair was noticing this, too, in the School of Social Work, where “a subtle but persistent decrease” led him to seek ways to attract males to his field.

Now Morgan is laying the groundwork for a possible enrollment of 15,000 students in the next five years, while also seeking to attain the coveted R1 ranking as one of the nation’s premier research institutions. As has been true since 1867, the status of Black males remains a paramount concern. In fact, so much so, that in the fall of 2024, Morgan President David K. Wilson established a task force whose name also reveals its mission: The State of Black Male Enrollment at Morgan: Causes and Recommendations. Professors Barnes and Sinclair are its co-chairs.

Around the nation, people are asking within education circles from HBCUs to the Ivys, from community colleges to graduate schools: Where are the men?

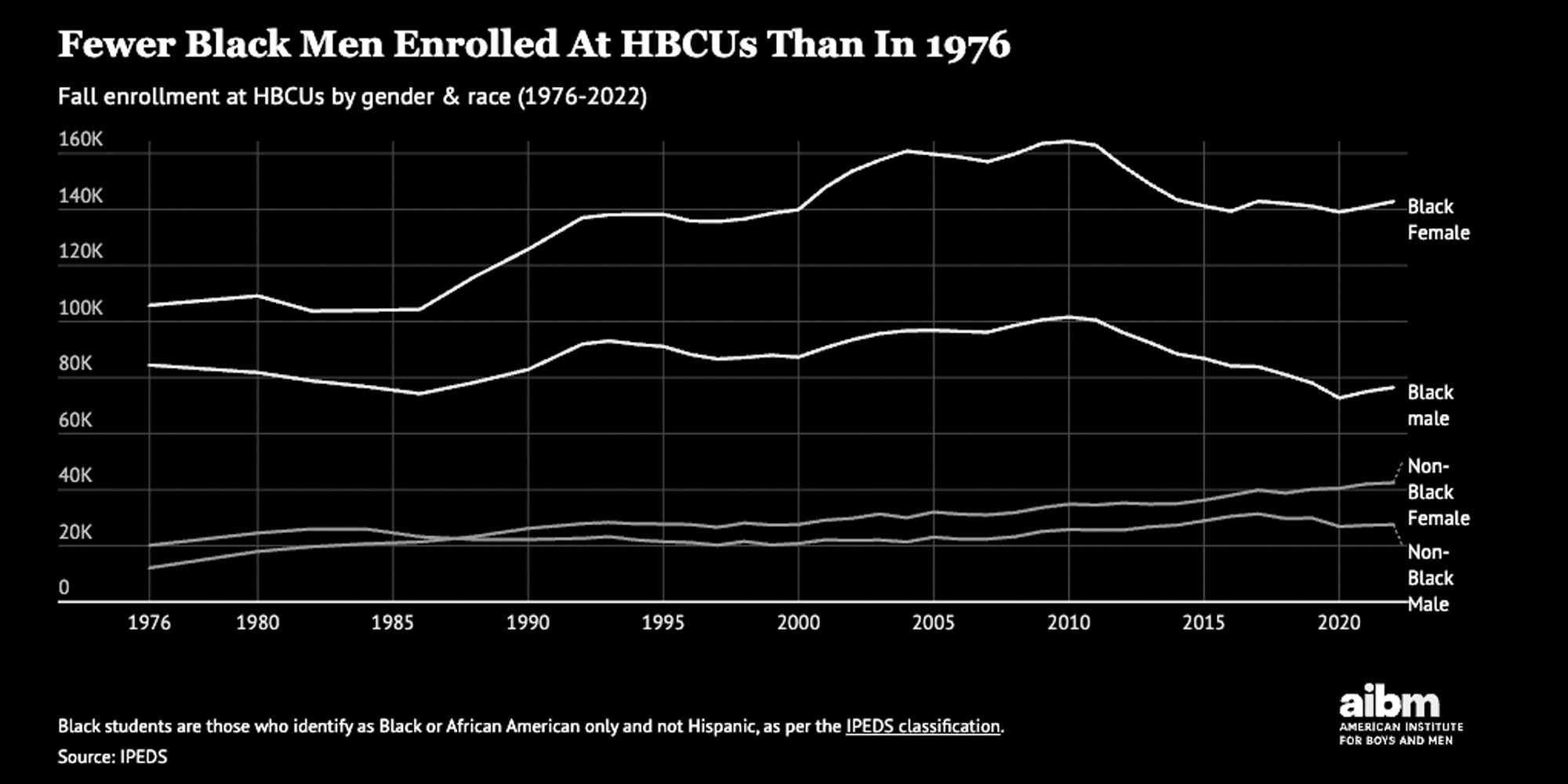

Black men account for only 26% of the students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), down from 38% in 1976.

Nearly 50-Year Trend

A declining enrollment of males — what The Chronicle of Higher Education describes as an “exodus of men away from college” — has been evident in higher education for nearly 50 years. In 1970, according to the U.S. Department of Education, male enrollment was 59%; by 2019, it was 43%. The Washington, DC-based American Institute for Boys and Men (AIBM) puts a finer point on the situation, focusing on who is earning degrees. In 1971, it says, women earned 43.5% of bachelor’s degrees and by 1980 had reached parity with men. Since then, however, women have overtaken men, and the gap has continued to grow. By 2020, according to AIBM, women earned 58% of bachelor’s degrees in the U.S. Though the issue has been percolating for some time, a sense of urgency to address it has been spurred in part by an AIBM report focused on Black males that was released in the summer of 2024 and by the alarmist headlines it engendered.

Its key, headline-grabbing finding was summarized this way:

Its key, headline-grabbing finding was summarized this way:

“Black men account for only 26% of the students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), down from 38% in 1976. In fact, there are fewer Black men enrolled at HBCUs today than in 1976. HBCUs have long served as valuable institutions for Black students, offering a unique environment that fosters academic achievement, mental well-being, and economic mobility.”

Many headlines associated the drop in Black male enrollment at HBCUs with declining admissions overall. That is hardly descriptive of Morgan, where admissions in recent years have been through the roof. Its fall 2024 enrollment of nearly 11,000 students made it the third largest HBCU, behind North Carolina A&T State University and Howard University.

President Wilson has observed that “only a few years ago, Morgan had one of the highest enrollments of Black males at HBCUs.” Under Morgan’s definition of “Black students” as “U.S. citizens of African descent,” the decline in enrollment of Black males at the National Treasure has been steady, though the Coronavirus pandemic exacerbated the situation. In 2009, Black males comprised 40% of all undergraduates at Morgan. By the fall of 2024, they were 29% of all undergraduates. Counting the Black undergraduate population alone, Black males were 44% in the fall of 2009 but dropped to 38% by the fall of 2024. By comparison, the number at Howard University was around 19% at that time.

Richard V. Reeves, Ph.D., the founding president of AIBM and co-author of the Institute’s report, addressed the situation in April during his appearance, along with Morgan’s own Professor M.K. Asante Jr. of the English and Language Arts Department, in Morgan’s Presidential Distinguished Speaker Series. The topic was “The Silent Crisis of America’s Boys and Men.” Said Reeves: “It’s taken higher education, with honorable exceptions, quite a long time to wake up to this new reality, to wake up to the fact that the gender gaps in higher education now almost always are where we need to be paying more attention to men.”

BLACK MEN AT MORGAN

Counting the Black undergraduate population alone, Black males were

Beyond ‘Either/Or’

Just as when President Barack Obama prioritized Black men with his My Brothers Keeper initiative in 2014, some women are wondering if Morgan’s — and higher education’s — emphasis on Black males will come at the expense of girls and women. Both Sinclair and Barnes insist that it will not.

“Supporting Black men does not mean you don’t support Black women. We can support Black women and their amazing achievements,” Dr. Sinclair said. “We know Black women are perhaps the most underappreciated group of people because they do so much for our communities, for our families. But Black men have been slowly falling behind.”

Dr. Reeves of AIBM has suggested that many institutions have been slow to act because of uncertainty about how to develop programs to recruit males, and provide the support they need to earn degrees, without undermining efforts that have been beneficial to females over the last half-century.

He and others have pointed to the developmental differences between males and females that shape their readiness to master skills that prepare them for college — or, as more than one person said, “Girls get their acts together earlier than boys.”

Edwin Johnson, Ph.D., a special assistant to the provost, and Morgan’s historian, offered a sweeping perspective of how “Black men have long been endangered” in the urban areas of the U.S. from which Morgan draws many of its students. Major factors, he said, were the so-called war on drugs that led to mass incarceration that disproportionately ensnared young Black males, and the loss of job opportunities in what were once major manufacturing hubs like Baltimore and cities in the Midwest.

Supporting Black men does not mean you don’t support Black women. We can support Black women and their amazing achievements…. But Black men have been slowly falling behind.

— Michael Sinclair, Ph.D.,

Associate Professor of Social Work, Morgan State University

Making the Case

At the inaugural meeting of Morgan’s task force in April 2025, faculty members, administrators and students shared research and their lived experiences as they considered competing influences that make college a low priority or not worth considering at all: K–12 schools with a dearth of male teachers, especially Black male teachers, as influencers; teachers telling Black males they are not college material — something that several tenured Morgan professors and an admissions officer said they were told in their formative years; a longing to belong; the notion that sitting in a classroom and relying on grants, loans and family support is unmanly.

Also discussed were pressure to prove manhood by earning money now rather than later — and by any means necessary; and living proof provided by people who have been quite successful in tech fields or in traditional trades like plumbing and electrical work that can be more lucrative than an entry-level job available to a college graduate — and without the debt that many college graduates accrue.

To address the need to belong, Dr. Barnes says, Morgan must place greater emphasis on opportunities that already exist for males, from sports teams to fraternities, from the choir to social justice and mentoring projects.

But how does Morgan make the case to restless males that upward mobility that college graduates can usually count on is worth delayed gratification? That’s a question the task force has begun wrestling with, and it intends to fine tune an answer rooted in Morgan’s history and mission.

“We have to sell what we’re selling, and what we’re selling is broader than just vocational skills,” Dr. Sinclair said in an interview after that inaugural meeting. He ticked off a list that included critical thinking, analysis and leadership.

As he shared the stage with Dr. Reeves in April, Professor Asante suggested making the connection between education and liberation.

“How can we make this education emancipatory?” he asked. “How can what we’re learning help get you free? How can it help free others?”

Dr. Sinclair would make a similar connection: “We have a responsibility to our communities of color to get the education (and) to apply it to uplift our communities. That’s the purpose of true education and knowledge. It’s not just to get a job.”

If that aim sounds a bit lofty, one recruiter said he offers straight talk to young men who have an end goal but have not quite figured out how to get from here to there. They hope they will achieve overnight success by being discovered via social media. For those who, for instance, want to become Baltimore’s next superstar recording artist, he breaks down how they are more likely to succeed by studying in Morgan’s music and business programs. He tells them, “The world we live in does not cater to us. If you don’t have credentials or contacts, you will likely go unnoticed.” Morgan, he says, can provide access to both.

The task force anticipates its work as a long-term institutional project, not something that will result in a report after several months of study.

“This can’t just be rhetoric,” Dr. Sinclair said. In the meantime, he said, he and Dr. Barnes have been hearing from the public, including parents, alumni and community-service organizations. “We have been inundated with a lot of people who simply want to help.”

Morgan’s task force anticipates its work as a long-term institutional project, not something that will result in a report after several months of study.

Journalist-scholar E.R. Shipp is an associate professor of Multimedia Journalism at Morgan State University and a 1996 recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for commentary.