By: Ferdinand Mehlinger

(Vinnie Bagwell Harriet Tubman maquette | Photo Credit: Adria Maysonett ©2023)

Sculptor Vinnie Bagwell, ’79, Creates Public Artwork to Inspire Her Community

Before Vinnie Bagwell ever lifted a chisel or molded clay, she was already sculpting something far more enduring: a vision. Raised in Westchester County, New York, and educated at Morgan State University in Baltimore, Bagwell didn’t enter the art world through a classroom or a gallery. She came by way of intuition, determination and a fierce belief in the power of storytelling. Today, operating from a converted carriage house perched above the historic Hudson River in Yonkers, the celebrated sculptor shapes more than just bronze. She shapes memory, justice and cultural legacy.

A 1979 Morgan graduate, Bagwell majored not in art but in Psychology, with a minor in mathematics. It was at Maryland’s largest Historically Black College or University (HBCU) that her life’s purpose began to crystallize, guided by the mentorship of George Carter, Ph.D., who was then chair of the Psychology Department. Under his influence, Bagwell began to channel her drive for service and humanity into a creative force, one that would eventually earn her national acclaim through award-winning public art commissions, and a mission to elevate collective consciousness through what she calls “legacy art.”

“Something we learned at Morgan was when we graduated to go out in the world and do something to help uplift the race,” Bagwell says. Answering that call to action has led her on a unique, creative, inspirational path, benefiting all who see her art.

The path has been winding at times. Bagwell worked in numerous industries, serving stints as a newspaper journalist, car salesperson, advertising executive and author — all before transforming an untapped passion into what would become a lifelong profession. At age 36, she began building skills to create some of the most compelling and emotionally affecting life-size sculptures in the modern African American repertoire.

Bagwell recalls the experience that crystallized her purpose in life. She attended an exhibit in Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1993, where more than 200 sculptors presented their best bronze works, not one of which represented an African American. The event left her feeling like someone had subconsciously or intentionally erased her people from the mainstream visual narratives.

Each sculpture, each story I immortalize, attempts to reflect our shared humanity.

— Vinnie Bagwell, Morgan Class of 1979

Her awareness woken, she found the same reality elsewhere.

“I’m looking around. I’m not seeing any public artworks about Black people at all,” Bagwell says. “…I’m seeing dead presidents, and war heroes…. I’m not seeing women.”

Thus began her quest to learn the art of sculpture.

“I learned the techniques I use in sculpture through intuition and trial and error,” says Bagwell. “This was before the internet. There was no YouTube. There was no Google. If you wanted to learn something you had to go to the library and look it up.” She continued: “So, you know you can do something, but the only question is what are your limitations? You start, and you invent things, and you move forward.”

Bagwell’s 32-year journey of invention has earned her a strong self-identity.

“I create art for public places. I am a representational-figurative sculptor,” she states. “That means I do people, and they look like a person.”

Finding a Style

In 2021, Bagwell completed what is arguably her most complex artistic achievement to date: “Enslaved Africans’ Rain Garden,” which stands near the Hudson River, in a sculpture garden in the revitalized waterfront district of Yonkers, New York. The five life-sized bronzes of the work draw on the real-life horror story lived by the African slaves and the indentured servants at Philipsburg Manor beginning in colonial times, not far from where the artist grew up and very near Sleepy Hollow, the town made famous by Washington Irving’s 1820 fictional horror tale. The project, 13 years in the making, was unveiled on Juneteenth 2021 to commemorate the legacy of the first enslaved Africans to be manumitted by law in the United States, 64 years before the Emancipation Proclamation.

Bagwell reveals the unspoken thoughts she has for those who view the public art: “I have snatched your eye. And now that I have your eye, I’m going to hold your eye and make you look at something you thought was going to be not so nice,” she says. “And you realize that there’s beauty…. And the beauty is that the descendants of these people have survived.”

Bagwell reveals the unspoken thoughts she has for those who view the public art: “I have snatched your eye. And now that I have your eye, I’m going to hold your eye and make you look at something you thought was going to be not so nice,” she says. “And you realize that there’s beauty…. And the beauty is that the descendants of these people have survived.”

“Enslaved Africans’ Rain Garden,” one of Bagwell’s numerous completed works and works in progress, came indirectly from the success of her first public artwork, a sculpture of musical great Ella Fitzgerald, which was commissioned by the City of Yonkers and was completed in 1996. Impressed by Bagwell’s work on the Fitzgerald likeness, Yonkers City Council Majority Leader Patricia McDow approached her at a Black History Month event in 2009, with the idea for the slave memorial.

By then, the artist had also completed her second public work, “Frederick Douglass Circle,” unveiled at Hofstra University, in Hempstead, New York, in 2008. Being self-schooled in sculpture allowed her to think outside of the box for the project.

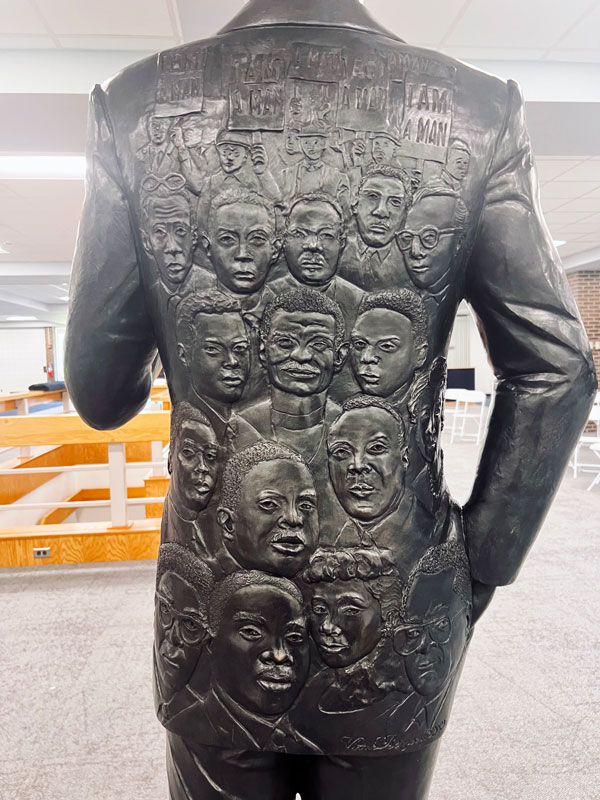

“My commission of Frederick Douglass at Hofstra University sits in the middle of an open plaza. People may approach him from every angle, so I wanted there to be something on the back. That was the first time that I tried using (bas-relief) sculpture on the surface of a sculpture,” Bagwell says. “I liked it…. After that, I decided, ‘I’m going to make this my style.’ I’ve found it’s a really good way to tell stories, people respond to it, and not many artists employ this technique.

“To sculpt figures naturally, realistically, is a gift. I learned early on that I had a skill for bas‑relief,” she continues. “I’m a mathematical person. I minored in math. I love math. Bas‑relief is a two‑dimensional sculpture that gives the illusion of three‑dimensional space. There’s a lot of math that goes into it, to discern the background, middle ground, foreground.”

Enduring Message

Other past projects of the artist include four sculptures commissioned by the District of Columbia Department of General Services: “What’s Going On!”, a likeness of music icon Marvin Gaye; “The Man in the Arena” (Theodore Roosevelt); “Contraband,” a tribute to the African slaves who escaped the Confederate South crossing to non-slave states during the American Civil War; and “The Immortals,” an homage to 85 musicians, displayed in the music corridor of Ron Brown College Preparatory High School, in Washington, DC. The City of Memphis commissioned her sculpture “Legacies,” which stands at Chickasaw Heritage Park. Director Ruben Santiago-Hudson commissioned Bagwell to create the piano artwork for August Wilson’s play, “The Piano Lesson” for the on-Broadway Signature Theatre in New York City. And “Liberté”, a 22-inch-high bronze, was included in the yearlong exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, at the new museum in Montgomery, Alabama, honoring that historic civil rights activism.

I’Satta (rear view) | Enslaved Africans Rain Garden, Yonkers NY | Photo credit: Vinnie Bagwell ©2022

In November 2022, Bagwell completed a life-sized sculpture in bronze of a civil rights icon, the Rev. James Lawson Jr., which is installed at Penn State University, Fayette. The commission was funded by Penn State and the Eberly Foundation.

Her current projects include the creation of an 18-foot angel named “Victory,” which will stand outside New York City’s Central Park, at Fifth Avenue and 103rd Street, and a seven-foot “Sojourner Truth, commissioned by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation in 2020, to celebrate the Women’s Suffrage Movement and the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, for the Walkway Over the Hudson, between Poughkeepsie and Highland, New York.

“These are human stories,” Bagwell says about her diverse oeuvre. “These are stories about resilience. These are stories about survival, struggle, achievement. (These) are the kinds of stories that inspire any and everyone. I don’t care how hard life is right now. You can survive adversity.”

“…This is why we make movies. This is why we make plays. This is why we do public art,” she adds. “You want to inspire people with other people’s stories.”

That purpose is reflected in her medium of choice, Bagwell says: “…bronze. Gold might gleam, but bronze is enduring. It tells stories for generations. Drawing from our shared history, I endeavor to make art that bridges divides, speaking to the universal experiences of resilience and survival.

“Each sculpture, each story I immortalize, attempts to reflect our shared humanity,” Bagwell says.

Instructed to Serve

Bagwell continues to heed the charge she received as an undergraduate at Morgan.

“I was taught that we go to school so that we can serve our community, and that’s the purpose of my work,” the artist says. “I want to be remembered for making not just art but great art that served my community.”

And her commitment to service transcends the studio. She speaks regularly at K–12 schools and colleges in Westchester and was the guest speaker for the Parren J. Mitchell-Benjamin A. Quarles Black History Month Convocation at Morgan in 2023.

A mentor to other women in art, Bagwell says she is often asked, “‘How do you get (to be) so good in the art arena (that) you can eat every day?’ ‘How do you make the transition from day job to working (as an artist) 100%?’ I’m like, ‘It’s called ‘the hustle.’”

But art offers much more than a meaningful career for its practitioners and entertainment for its consumers, Bagwell emphasizes.

“Art can do more than just please the eye. It ignites discussions, challenges perceptions and inspires future generations,” the artist states. “As we forge ahead, we must harness the collective strength of our narratives and engage in the dialogues that truly matter. A brighter future is not just possible but achievable. And art is the compass that guides us towards it.”

Vinnie Bagwell is the quintessential example of God-given talent. Though (she was) not formally trained as a sculptor, Bagwell’s works are easily among the most beautiful creations ever produced within the medium. I’ve often wondered if Augusta Savage is revisiting us in Vinnie Bagwell. Like the artists of the Harlem Renaissance, Bagwell insists that the African American experience (be) included within the narrative and artistic landscape of American history, while simultaneously creating artistic brilliance that implores everyone to pause and marvel at its magnificence.

– Edwin T. Johnson, Ph.D.

Special Assistant to the Provost and University Historian

Public Art Matters

“Representation matters, in all honesty and in all venues. The public art dotting landscapes across American cities provide aesthetic relief, natural beauty and points of conversation for residents and visitors to any urban location. Here at Morgan, the work of James E. Lewis inaugurated a steady flow of public art that speaks to Maryland, Baltimore and Morgan history while gently introducing the presence and permanence of African American people into the campus. Fast forward to the 21st century: self-taught artist George Nock (Morgan Class of 1969) launched a one-man crusade to memorialize the epic legacy of Coach Eddie Hurt and Coach (Earl) Banks.

Statues, memorials and sculptures captivate the public and simultaneously educate passively about a time, event, person, people or community of significance to the locale where the art stands.”

– Ida E. Jones, Ph.D.

Associate Director of Special Collections and University Archivist

Legends in Bronze

Unveiled in October 2025, Legends Plaza, a nearly 2,000-square-foot enclosure on Morgan Commons, features six-foot bronze statues of Head Coach Edward P. (“Eddie”) Hurt and Head Coach Earl C. (“Papa Bear”) Banks, who led Morgan football teams during an era of greatness that stretched from the late 1920s through the early 1970s.

George Nock, the sculptor and designer for Legends Plaza, was a starting player on Coach Banks’ Bears from 1965 to 1968 and played four years as a running back in the National Football League. The self-taught artist, who passed away in 2020, said he took on the project to add to his own artistic legacy as well as inspire current Morgan students to excellence.

Retired U.S. Army Lt. Col. David F. Mack, a Morgan graduate in the Class of 1971, has established a fund to support the casting of a plaque recognizing Nock’s work as the creator of the Legends Plaza sculptures.